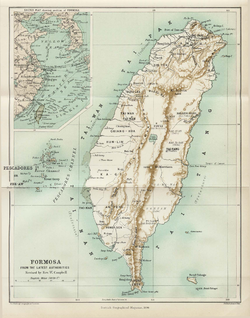

History of Taiwan

Part of a series on |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prehistory 50,000 BC – AD 1624 | ||||||||

| Kingdom of Middag 1540 – 1732 | ||||||||

| Dutch rule 1624 – 1662 | ||||||||

| Spanish rule 1626 – 1642 | ||||||||

| Kingdom of Tungning 1662 – 1683 | ||||||||

| Qing Dynasty rule 1683 – 1895 | ||||||||

| Republic of Formosa 1895 | ||||||||

| Japanese rule 1895 – 1945 | ||||||||

| Republic of China rule 1945 – present | ||||||||

|

Categories

|

||||||||

|

Lists

|

||||||||

|

Related

|

- This article discusses the history of Taiwan (including Penghu). For history of the polity which currently governs Taiwan, see history of the Republic of China.

Taiwan (excluding Penghu) was first populated by Austronesian people. It was colonized by the Dutch in the 17th century, followed by an influx of Han Chinese including Hakka immigrants from areas of Fujian and Guangdong of mainland China, across the Taiwan Strait. The Spanish also built a settlement in the north for a brief period, but were driven out by the Dutch in 1642.

In 1662, Koxinga (Zheng Cheng-gong), a Ming Dynasty loyalist, defeated the Dutch and established a base of operations on the island. Zheng's forces were later defeated by the Qing Dynasty in 1683. From then, parts of Taiwan became increasingly integrated into the Qing Empire before it ceded the island to Japan in 1895 following the First Sino-Japanese War. Taiwan produced rice and sugar to be exported to Japan and also served as a base for the Japanese colonial expansion into Southeast Asia and the Pacific during World War II. Japanese imperial education was implemented in Taiwan and many Taiwanese also fought for Japan during the war.

Following World War II, the Republic of China (ROC), under the Kuomintang (KMT) became the governing polity on Taiwan. In 1949, after losing control of mainland China following the Chinese civil war, the ROC government under the KMT withdrew to Taiwan and Chiang Kai-shek declared martial law. Japan formally renounced all territorial rights to Taiwan in 1952 in the San Francisco Peace Treaty. The KMT ruled Taiwan as a single-party state for forty years, until democratic reforms were mandated during the final year of authoritarian rule under Chiang Ching-kuo. The reforms were promulgated under Chiang's successor, Lee Teng-hui, which culminated in the first ever direct presidential election in 1996. In 2000, Chen Shui-bian was elected the president, becoming the first non-KMT president on Taiwan. The 2008 election of President Ma Ying-jeou marked the second peaceful transfer of power, this time back to the KMT.

|

Timeline of Taiwan's History

|

Prehistoric settlement

Taiwan is estimated by anthropologists to have been populated for approximately 30,000 years.[1][2] Little is known about the original inhabitants, but distinctive jadeware, and corded pottery of the Changpin, Beinan and Tapenkeng (Dapenkeng) cultures show a marked diversity in the island's early inhabitants. Hemp fibre imprints have been found in pottery shards over 10,000 years old in Taiwan.[3] Taiwan's aboriginal peoples are classified as belonging to the Austronesian ethno-linguistic group of people, a linguistic group that stretches as far west as Madagascar, and even as far as Easter Island in the east and to New Zealand in the south with Hawaii as the northern most point. Even if there is evidence (e.g., Bellwood 1997) that speakers of pre-Proto-Austronesian migrated from the South Chinese mainland to Taiwan at some time around 8,000 years ago, it is believed that Austronesian culture on Taiwan began about 6,000 years ago (Blust 1999) and spread to the entire region now encompassed by the Austronesian languages (Diamond 2000).

History of the indigenous peoples

Indigenous Taiwanese or indigenous peoples (Chinese: 原住民; pinyin: yuánzhùmín; Wade–Giles: yüan2-chu4-min2; Taiwanese Pe̍h-oē-jī: gôan-chū-bîn, literally "original inhabitants") are the native peoples of Taiwan. Their ancestors are believed to have been living on the islands for approximately 8,000 years before major Han Chinese immigration began in the 1600s.[4] The Taiwanese Aborigines are Austronesian peoples, with linguistic and genetic ties to other Austronesian ethnic groups, such as peoples of the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Oceania.[5] Taiwan's Austronesian speakers were traditionally distributed over much of the island's rugged central mountain range and concentrated in villages along the alluvial plains. Today, the bulk of the contemporary Taiwanese Aborigine population reside in the mountains and the cities. The issue of an ethnic identity unconnected to the Asian mainland has become one thread in the discourse regarding the political identity of Taiwan. The total population of Aborigines on Taiwan is around 458,000 as of January 2006,[6] which is approximately 2% of Taiwan's population.

For centuries Taiwan's indigenous peoples experienced economic competition and military conflict with a series of conquering peoples. As a result of these intercultural dynamics, as well as more dispassionate economic processes, many of these tribes have been linguistically and culturally assimilated. The result has been varying degrees of language death and loss of original cultural identity. For example, of the approximately 26 known languages of the Taiwanese Aborigines (collectively referred to as the Formosan languages), at least ten are extinct, another five are moribund[7] and several others are to some degree endangered. These languages are of unique historical significance, since most historical linguists consider Taiwan as the original homeland of the Austronesian language family.[8]

Today the indigenous peoples of Taiwan face economic and social barriers, including a high unemployment rate and substandard education. They have been actively seeking a higher degree of self-determination and economic development since the early 1980s. In 1996 the Council of Indigenous Peoples was promoted to a ministry-level rank within the Executive Yuan. A revival of ethnic pride has been expressed in many ways by aborigines, including incorporating elements of their culture into commercially successful pop music. Efforts are underway by indigenous communities to revive traditional cultural practices and preserve their languages. The aboriginal tribes have also become extensively involved in the tourism and eco-tourism industries.

Early history

Despite Taiwan being rumored as the fabled "Island of Dogs," "Island of Women," or any of the other fabled island thought, by Han literati, to lie beyond the seas, Taiwan was officially regarded by Qing Emperor Kangxi as "a ball of mud beyond the pale of civilization" and did not appear on any map of the imperial domain until 1683.[9] The act of presenting a map to the emperor was equal to presenting the lands of the empire. It took several more years before the Qing court would recognize Taiwan as part of the Qing realm. Prior to the Qing Dynasty, China was conceived as a land bound by mountains, rivers and seas. The idea of an island as a part of China was unfathomable to the Han prior to the Qing frontier expansion effort of the 17th Century.[10]

Dutch and Spanish rule

Portuguese sailors, passing Taiwan in 1544, first jotted in a ship's log the name of the island "Ilha Formosa", meaning Beautiful Island. In 1582 the survivors of a Portuguese shipwreck spent ten weeks battling malaria and Aborigines before returning to Macau on a raft.[11]

Dutch traders, in search of an Asian base first arrived on the island in 1623 to use the island as a base for Dutch commerce with Japan and the coastal areas of China. The Spanish and allies established a settlement at Santissima Trinidad, building Fort San Salvador on the northwest coast of Taiwan near Keelung in 1626 which they occupied until 1642 when they were driven out by a joint Dutch-Aborigine invasion force.[12] They also built a fort in Tamsui (1628) but had already abandoned it by 1638. The Dutch later erected Fort Anthonio on the site in 1642, which still stands (now part of the Fort San Domingo museum complex).

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) administered the island and its predominantly aboriginal population until 1662, setting up a tax system, schools to teach romanized script of aboriginal languages and evangelizing.[13] Although its control was mainly limited to the western plain of the island, the Dutch systems were adopted by succeeding occupiers.[14] The first influx of migrants from coastal Fujian came during the Dutch period, in which merchants and traders from the mainland Chinese coast sought to purchase hunting licenses from the Dutch or hide out in aboriginal villages to escape the Qing authorities. Most of the immigrants were young single males who were discouraged from staying on the island often referred to by Han as "The Gate of Hell" for its reputation in taking the lives of sailors and explorers.[15]

The Dutch originally sought to use their castle Zeelandia at Tayowan as a trading base between Japan and China, but soon realized the potential of the huge deer populations that roamed in herds of thousands along the alluvial plains of Taiwan's western regions.[16] Deer were in high demand by the Japanese who were willing to pay top dollar for use of the hides in samurai armor. Other parts of the deer were sold to Han traders for meat and medical use. The Dutch paid aborigines for the deer brought to them and tried to manage the deer stocks to keep up with demand. The Dutch also employed Han to farm sugarcane and rice for export, some of these rice and sugarcane products reached as far as the markets of Persia. Unfortunately the deer the aborigines had relied on for their livelihoods began to disappear forcing the aborigines to adopt new means of survival. The Dutch built a second administrative castle on the main island of Taiwan in 1633 and set out to earnestly turn Taiwan into a Dutch colony.[8]

The first order of business was to punish villages that had violently opposed the Dutch and unite the aborigines in allegiance with the VOC. The first punitive expedition was against the villages of Baccloan and Mattauw, north of Saccam near Tayowan. The Mattauw campaign had been easier than expected and the tribe submitted after having their village razed by fire. The campaign also served as a threat to other villages from Tirossen (modern Chiayi) to Lonkjiaow (Heng Chun). The 1636 punitive attack on Lamay Island (Hsiao Liuchiu) in response to the killing of the shipwrecked crew of the Beverwijck and the Golden Lion ended ten years later with the entire aboriginal population of 1100 removed from the island including 327 Lamayans killed in a cave, having been trapped there by the Dutch and suffocated in the fumes and smoke pumped into the cave by the Dutch and their allied aborigines from Saccam, Soulang and Pangsoya.[17] The men were forced into slavery in Batavia (Java) and the women and children became servants and wives for the Dutch officers. The events on Lamay changed the course of Dutch rule to work closer with allied aborigines, though there remained plans to depopulate the outlying islands.[18]

Ming loyalist rule

Manchu forces broke through Shanhai Pass in 1644 and rapidly overwhelmed the Ming Dynasty. In 1661, a naval fleet led by the Ming loyalist Koxinga, arrived in Taiwan to oust the Dutch from Zeelandia and establish a pro-Ming base in Taiwan.[19]

Koxinga was born to Zheng Zhilong, a Chinese merchant and pirate, and Tagawa Matsu, a Japanese woman, in 1624 in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. He was raised there until seven and moved to Quanzhou, in the Fujian province of China. In a family made wealthy from shipping and piracy, Koxinga inherited his father's trade networks, which stretched from Nagasaki to Macao. Following the Manchu advance on Fujian, Koxinga retreated from his stronghold in Amoy (Xiamen) and besieged Taiwan in the hope of establishing a strategic base to marshal his troops to retake his base at Amoy. In 1662, following a nine month siege, Koxinga captured the Dutch fortress Zeelandia and Taiwan became his base (see Kingdom of Tungning).[20] Concurrently the last Ming pretender had been captured and killed by General Wu Sangui, extinguishing any hope Koxinga may have had of re-establishing the Ming Empire. He died four months thereafter in a fit of madness after learning of the cruel killings of his father and brother at the hands of the Manchus. Other accounts are more straightforward, attributing Koxinga's death to a case of malaria.[21]

Qing Dynasty rule

In 1683, following a naval engagement with Admiral Shi Lang, one of Koxinga's father's trusted friends, Koxinga's grandson Zheng Keshuang submitted to Qing Dynasty control.

Despite the expense of the military and diplomatic campaign that brought Taiwan into the imperial realm, the general sentiment in Beijing was ambivalent. The point of the campaign had been to destroy the Zheng-family regime, not to conquer the island. Qing Emperor Kangxi expressed the sentiment that Taiwan was "the size of a pellet; taking it is no gain; not taking it is no loss" (彈丸之地。得之無所加,不得無所損). His ministers counseled that the island was "a ball of mud beyond the sea, adding nothing to the breadth of China" (海外泥丸,不足為中國加廣), and advocated removing all the Chinese to mainland China and abandoning the island. It was only the campaigning of admiral Shi Lang and other supporters that convinced the Emperor not to abandon Taiwan. [22] Koxinga's followers were forced to depart from Taiwan to the more unpleasant parts of Qing controlled land. By 1682 there were only 7000 Chinese left on Taiwan as they had intermarried with aboriginal women and had property in Taiwan. The Koxinga reign had continued the tax systems of the Dutch, established schools and religious temples.

From 1683, the Qing Dynasty ruled Taiwan as a prefecture and in 1875 divided the island into two prefectures, north and south. In 1885, the island was made into a separate Chinese province.

The Qing authorities tried to limit immigration to Taiwan and barred families from traveling to Taiwan to ensure the immigrants would return to their families and ancestral graves. Illegal immigration continued, but many of the men had few prospects in war weary Fujian and thus married locally, resulting in the idiom "Tangshan (Chinese) grandfather no Tangshan grandmother" (有唐山公無唐山媽). The Qing tried to protect aboriginal land claims, but also sought to turn them into tax paying subjects. Chinese and tax paying aborigines were barred from entering the wilderness which covered most of the island for the fear of raising the ire of the non taxpaying, highland aborigines and inciting rebellion. A border was constructed along the western plain, built using pits and mounds of earth, called "earth cows", to discourage illegal land reclamation.

From 1683 to around 1760, the Qing government limited immigration to Taiwan. Such restriction was relaxed following the 1760s and by 1811 there were more than two million Chinese immigrants on Taiwan. In 1875 the Taipei government (台北府) was established, under the jurisdiction of Fujian province. Also, there had been various conflicts between Chinese immigrants. Most conflicts were between Han from Fujian and Han from Guangdong, between people from different areas of Fujian, between Han and Hakka settlers, or simply between people of different surnames engaged in clan feuds. Because of the strong provincial loyalties held by these immigrants, the Qing government felt Taiwan was somewhat difficult to govern. Taiwan was also plagued by foreign invasions. In 1840 Keelung was invaded by the British in the Opium War, and in 1884 the French invaded as part of the Sino-French War. Because of these incursions, the Qing government began constructing a series of coastal defenses and on 12 October 1885 Taiwan was made a province, with Liu Mingchuan serving as the first governor. He divided Taiwan into eleven counties and tried to improve relations with the aborigines. He also developed a railway from Taipei to Hsinchu, established a mine in Keelung, and built an arsenal to improve Taiwan's defensive capability against foreigners.

Following a shipwreck of a Ryūkyūan vessel on the southeastern tip of Taiwan in winter of 1871, in which the heads of 54 crew members were taken by the aboriginal Taiwanese Paiwan people in Mutan village (牡丹社), the Japanese sought to use this incident as a pretext to have the Qing formally acknowledge Japanese sovereignty over the Ryuku islands as a Japanese prefecture and to test reactions to potential expansion into Taiwan. According to records from Japanese documents, Mao Changxi (毛昶熙) and Dong Xun (董恂), the Qing ministers at Zongli Yamen (總理衙門) who handled the complaints from Japanese envoy Yanagihara Sakimitsu (柳原前光) replied first that they had heard only of a massacre of Ryūkyūans, not of Japanese, and quickly noted that Ryūkyū was under Chinese suzerainty, therefore this issue was not Japan's business. In addition, the governor-general of the Qing province Fujian had rescued the survivors of the massacre and returned them safely to Ryūkyū. The Qing authorities explained that there were two kinds of aborigines on Taiwan: those governed by the Qing, and those unnaturalized "raw barbarians... beyond the reach of Qing government and customs." They indirectly hinted that foreigners traveling in those areas settled by indigenous people must exercise caution. After the Yanagihara-Yamen interview, the Japanese took their explanation to mean that the Qing government had not opposed Japan's claims to sovereignty over the Ryūkyū Islands, disclaimed any jurisdiction over Aboriginal Taiwanese, and had indeed consented to Japan's expedition to Taiwan.[23] The Qing Dynasty made it clear to the Japanese that Taiwan was definitely within Qing jurisdiction, even though part of that island's aboriginal population was not yet under the influence of Chinese culture. The Qing also pointed to similar cases all over the world where an aboriginal population within a national boundary was not completely subjugated by the dominant culture of that country.

The Japanese nevertheless launched an expedition to Mutan village with a force of 2000 soldiers in 1874. The number of casualties for the Paiwan was about 30, and that for the Japanese was 543; 12 Japanese soldiers were killed in battle and 531 by disease. Eventually, the Japanese withdrew just before the Qing Dynasty sent 3 divisions of forces (9000 soldiers) to reinforce Taiwan. This incident caused the Qing to re-think the importance of Taiwan in their maritime defense strategy and greater importance was placed on gaining control over the wilderness regions.

On the eve of the Sino-Japanese War about 45 percent of the island was administered under direct Qing administration while the remaining was lightly populated by Aborigines[24]. In a population of around 2.5 million, about 2.3 million were Han Chinese and the remaining two hundred thousand were classified as members of various indigenous tribes.

As part of the settlement for losing the Sino-Japanese War, The Qing empire ceded the island of Taiwan and Penghu to Japan on 17 April 1895, according to the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The loss of Taiwan would become a rallying point for the Chinese nationalist movement in the years that followed.[25]

Japanese rule

Japan had sought to claim sovereignty over Taiwan (known to them as Takasago Koku) since 1592, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi undertook a policy of overseas expansion and extending Japanese influence southward,[26] to the west, was invaded and an attempt to invade Taiwan and subsequent invasion attempts were to be unsuccessful due mainly to disease and attacks by aborigines on the island. In 1609, the Tokugawa Shogunate sent Harunobu Arima on an exploratory mission of the island. In 1616, Murayama Toan led an unsuccessful invasion of the island. The Mudan Incident of 1871 occurred when an Okinawan vessel shipwrecked on the southern tip of Taiwan and the crew of 54 were beheaded by Paiwan Aborigines. When Japan sought compensation from Qing China, the court rejected compensation on the account that they didn't have jurisdiction over the island. This was to lead to Japan testing the situation for colonizing the island and in 1874 an expedition force of 3,000 (or 2,000) troops were sent to the island, but were not able to take it. It was not until the defeat of the Chinese navy during the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894-95 for Japan to finally realize possession of Taiwan and the shifting of Asian dominance from China to Japan. The Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed on 17 April 1895, ceding Taiwan and Penghu over to Japan, which would rule the island for 50 years until its defeat in World War II.

After receiving sovereignty of Taiwan, the Japanese feared military resistance from both Taiwanese and Aborigines who followed the establishment by the local elite of the short-lived Republic of Formosa. Taiwan's elite hoped that by declaring themselves a republic the world would not stand by and allow a sovereign state to be invaded by the Japanese, thereby allying with the Qing. The plan quickly turned to chaos as standard Green troops and ethnic Yue soldiers took to looting and pillage. Given the choice between chaos at the hands of Chinese or submission to the Japanese, the Taipei elite sent Koo Hsien-jung to Keelung to invite the advancing Japanese forces to proceed to Taipei and restore order.[27]

Armed resistance was sporadic, yet at times fierce, but was largely crushed by 1902, although relatively minor rebellions occurred in subsequent years, including the Ta-pa-ni incident of 1915 in Tainan county.[28] Nonviolent means of resistance began to take place of armed rebellions and the most prominent organization was the Taiwanese Cultural Association (台灣文化協會), founded in 1921. Taiwanese resistance was caused by several different factors (e.g., the Taishō Democracy). Some were goaded by Chinese nationalism, while others contained nascent Taiwanese self-determination.[29] Rebellions were often caused by a combination of the effects of unequal colonial policies on local elites and extant millenarian beliefs of the local Taiwanese and plains Aborigines. Aboriginal resistance to the heavy-handed Japanese policies of acculturation and pacification lasted up until the early 1930s.[30] The last major Aboriginal rebellion, the Musha Uprising (Wushe Uprising) in late 1930 by the Atayal people angry over their treatment while laboring in the burdensome job of camphor extraction, launched the last headhunting party in which over 150 Japanese officials were killed and beheaded during the opening ceremonies of a school. The uprising, led by Mona Rudao, was crushed by 2,000-3,000 Japanese troops and Aboriginal auxiliaries with the help of poison gas.[31]

Japanese colonization of the island fell under three stages. It began with an oppressive period of crackdown and paternalistic rule, then a dōka (同化) period of aims to treat all people (races) alike proclaimed by Taiwanese Nationalists who were inspired by the Self-Determination of Nations (民族自決) proposed by Woodrow Wilson after World War I, and finally, during World War II, a period of kōminka (皇民化), a policy which aimed to turn Taiwanese into loyal subjects of the Japanese emperor.

Reaction to Japanese rule among the Taiwanese populace differed. Some felt that the safety of personal life and property was of utmost importance and went along with the Japanese colonial authorities. The second group of Taiwanese were eager to become imperial subjects, believing that such action would lead to equal status with Japanese nationals. The third group was influenced Taiwan independence and tried to get rid of the Japanese colonials to establish a native Taiwanese rule. The fourth group on the other hand were influenced by Chinese nationalism and fought for the return of Taiwan to Chinese rule. From 1897 onwards the latter group staged many rebellions, the most famous one being led by Luo Fuxing (羅福星), who was arrested and executed along with two hundred of his comrades in 1913. Luo himself was a member of the Tongmenghui, an organization founded by Sun Yat-sen and was the precursor to the Kuomintang.[32]

Initial infrastructural development took place quickly. The Bank of Taiwan was established in 1899 to encourage Japanese private sectors, including Mitsubishi and the Mitsui Group, to invest in Taiwan. In 1900, the third Taiwan Governor-General passed a budget which initiated the building of Taiwan's railroad system from Kirun (Keelung) to Takao (Kaohsiung). By 1905 the island had electric power supplied by water power in Sun-Moon Lake, and in subsequent years Taiwan was considered the second-most developed region of East Asia (after Japan). By 1905, Taiwan was financially self-sufficient and had been weaned off of subsidies from Japan's central government.

Under the governor Shimpei Goto's rule, many major public works projects were completed. The Taiwan rail system connecting the south and the north and the modernizations of Kirun (Keelung) and Takao (Kaohsiung) ports were completed to facilitate transport and shipping of raw material and agricultural products.[33] Exports increased by fourfold. 55% of agricultural land was covered by dam-supported irrigation systems. Food production had increased fourfold and sugar cane production had increased 15-fold between 1895 to 1925 and Taiwan became a major foodbasket serving Japan's industrial economy. The health care system was widely established and infectious diseases were almost completely eradicated. The average lifespan for a Taiwanese resident would become 60 years by 1945.[34]

In October 1935, the Governor-General of Taiwan held an "Exposition to Commemorate the 40th Anniversary of the Beginning of Administration in Taiwan," which served as a showcase for the achievements of Taiwan's modernization process under Japanese rule. This attracted worldwide attention, including the Republic of China's KMT regime which sent the Japanese-educated Chen Yi to attend the affair. He expressed his admiration about the efficiency of Japanese government in developing Taiwan, and commented on how lucky the Taiwanese were to live under such effective administration. Somewhat ironically, Chen Yi would later become the ROC's first Chief Executive of Taiwan, who would be infamous for the corruption that occurred under his watch.

The later period of Japanese rule saw a local elite educated and organized. During the 1930s several home rule groups were created at a time when others around the world sought to end colonialism. In 1935, the Taiwanese elected their first group of local legislators. By March 1945, the Japanese legislative branch hastily modified election laws to allow Taiwanese representation in the Japanese Diet.

As Japan embarked on full-scale war in China in 1937, it expanded Taiwan's industrial capacity to manufacture war material. By 1939, industrial production had exceeded agricultural production in Taiwan. At the same time, the "kominka" imperialization project was put under way to instill the "Japanese Spirit" in Taiwanese residents, and ensure the Taiwanese would remain loyal subjects of the Japanese Emperor ready to make sacrifices during wartime. Measures including Japanese-language education, the option of adopting Japanese names, and the worship of Japanese religion were instituted. In 1943, 94% of the children received 6-year compulsory education. From 1937 to 1945, 126,750 Taiwanese joined and served in the military of the Japanese Empire, while a further 80,433 were conscripted between 1942 to 1945. Of the sum total, 30,304, or 15%, died in Japan's war in Asia.

The Imperial Japanese Navy operated heavily out of Taiwan. The "South Strike Group" was based out of the Taihoku Imperial University (now National Taiwan University) in Taiwan. Many of the Japanese forces participating in the Aerial Battle of Taiwan-Okinawa were based in Taiwan. Important Japanese military bases and industrial centers throughout Taiwan, like Takao (now Kaohsiung), were targets of heavy American bombing.

In 1942, after the United States entered in war against Japan and on the side of China, the Chinese government under the KMT renounced all treaties signed with Japan before that date and made Taiwan's return to China (as with Manchuria) one of the wartime objectives. In the Cairo Declaration of 1943, the Allied Powers declared the return of Taiwan to China as one of several Allied demands. In 1945, Japan unconditionally surrendered with signing of the instrument of surrender and ended its rule in Taiwan as the territory was put under the administrative control of the Republic of China government in 1945 by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration [35]. Per the provisions in Article 2 of San Francisco Peace Treaty, the Japanese formally renounced the territorial sovereignty of Taiwan and Penghu islands, and the treaty was signed in 1951 and came into force in 1952. Due to the fact China had no one certain legitimate government in power at the time of treaty signing, none of the governments claiming to be the rightful representative of China that time was invited to the treaty signing as neither had shown full and complete legal capacity in entering into an international legally binding agreement. Taiwan and Penghu Islands, as of the moment when the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into force, had become a limbo cession with its political status undetermined.[35]

Republic of China rule

Nationalist party period

Under martial laws

The Republic of China established Taiwan Provincial Government in September 1945[36] and proclaimed on October 25, 1945 as "Taiwan Retrocession Day." This is the day in which the Japanese troops surrendered. The validity of the proclamation is subject to some debate, with some supporters of Taiwan independence arguing that it is invalid, and that the date only marks the beginning of military occupation that persists to the present.[37][38] During the immediate postwar period, the Kuomintang (KMT) administration on Taiwan was repressive and extremely corrupt compared with the previous Japanese rule, leading to local discontent. Anti-mainlander violence flared on February 28, 1947, prompted by an incident in which a cigarette seller was injured and a passerby was indiscriminately shot dead by Nationalist authorities.[39] During the ensuing crackdown by the KMT administration in what became known as the 228 incident, hundreds or thousands of people were killed, and the incident became a taboo topic of discussion for the entire martial law era.

From the 1930s onward a civil war was underway in mainland China between Chiang Kai-shek's ROC government and the Communist Party of China led by Mao Zedong. When the civil war ended in 1949, 2 million refugees, predominantly from the Nationalist government, military, and business community, fled to Taiwan. On October 1, 1949 the People's Republic of China (P.R.C.) was founded in mainland China by the victorious communists; several months before, Chiang Kai-shek had established a provisional ROC capital in Taipei and moved his government there from Nanjing. Under Nationalist rule, the mainlanders dominated the government and civil services.[40]

Chiang Kai-shek died, in April 1975, and was succeeded to the presidency by Yen Chia-kan while his son Chiang Ching-kuo succeeded to the leadership of the Kuomintang (opting to take the title "Chairman" rather than the elder Chiang's title of "Director-General"). He set the stage that led to incredible economic successes of the territories starting in the mid 1980s. In 1987, Chiang ended martial law and allowed family visits to mainland China. His administration saw a gradual loosening of political controls and opponents of the Nationalists were no longer forbidden to hold meetings or publish papers. Opposition political parties, though still illegal, were allowed to form. When the Democratic Progressive Party was established in 1986, President Chiang decided against dissolving the group or persecuting its leaders, but its candidates officially ran in elections as independents in the Tangwai movement.

In an effort of bringing more Taiwan-born citizens into government services, Chiang Ching-kuo hand-picked Lee Teng-hui as vice-president of the Republic of China, first-in-the-line of succession to the presidency. However, it is unclear whether he was in favor of having Lee succeeding him as Chairman of the Nationalist Party.

Economic developments

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, post-war economic conditions compounded with the then-ongoing Chinese Civil War caused severe inflation across mainland China and in Taiwan, made worse by disastrous currency reforms and corruption. This gave way to the reconstruction process and new reforms.

The KMT took control of Taiwan's monopolies that had been owned by the Japanese during colonial period. Approximately 91% of Taiwan's GNP was nationalized. Also, Taiwanese investors lost their claim to the Japanese bond certificates they possessed. These real estate holdings as well as American aid such as the China Aid Act and the Chinese-American Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction helped to ensure that Taiwan would recover quickly from war. The Kuomintang government also moved the entire gold reserve from the Chinese mainland to Taiwan, and used this reserve to back the newly-issued New Taiwan Dollar to stabilize the new currency and put a stop to hyperinflation.

The KMT authorities implemented a far-reaching and highly successful land reform program on Taiwan during the 1950s. The 375 Rent Reduction Act alleviated tax burden on peasants and another act redistributed land among small farmers and compensated large landowners with commodities certificates and stock in state-owned industries. Although this left some large landowners impoverished, others turned their compensation into capital and started commercial and industrial enterprises. These entrepreneurs were to become Taiwan's first industrial capitalists. Together with businessmen who fled from mainland China, they once again revived Taiwan's prosperity previously ceased along with Japanese withdrawal and managed Taiwan's transition from an agricultural to a commercial, industrial economy.

From 1950 to 1965, Taiwan received a total of $1.5 billion in economic aid and $2.4 billion in military aid from the United States. In 1965 all American aid ceased when Taiwan had established a solid financial base.[41] Having accomplished that, the government then adopted policies for building a strong export-driven economy, with state projects such as the Ten Major Construction Projects that provided the infrastructure required for such ventures. Taiwan has developed steadily into a major international trading power with more than $218 billion in two-way trade and one of the highest foreign exchange reserves in the world. Tremendous prosperity on the island was accompanied by economic and social stability. Taiwan's phenomenal economic development earned it a spot as one of the Four Asian Tigers.

Democratic reforms

Until the early 1970s, the Republic of China was recognized as the sole legitimate government of China by the United Nations and most Western nations, refusing to recognize the People's Republic of China on account of the Cold War. The KMT ruled Taiwan under martial law until the late 1980s, with the stated goal of being vigilant against Communist infiltration and preparing to retake mainland China. Therefore, political dissent was not tolerated.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were a turbulent time for Taiwanese as many of the people who had originally been oppressed and left behind by economic changes became members of the Taiwan's new middle class. Free enterprise had allowed native Taiwanese to gain a powerful bargaining chip in their demands for respect for their basic human rights. The Kaohsiung Incident would be a major turning point for democracy in Taiwan.

Taiwan also faced setbacks in the international sphere. In 1971, the ROC government walked out of the United Nations shortly before it recognized the PRC government in Beijing as the legitimate holder of China's seat in the United Nations. The ROC had been offered dual representation, but Chiang Kai-shek demanded to retain a seat on the UN Security Council, which was not acceptable to the PRC. Chiang expressed his decision in his famous "the sky is not big enough for two suns" speech. In October 1971, Resolution 2758 was passed by the UN General Assembly and "the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek" (and thus the ROC) were expelled from the UN and replaced as "China" by the PRC. In 1979, the United States switched recognition from Taipei to Beijing.

Chiang Kai-shek was succeeded by his son Chiang Ching-kuo. When the younger Chiang came to power he began to liberalize the system. In 1986, the Democratic Progressive Party was formed. This organization was formed illegally, and inaugurated as the first party in opposition to Taiwan. This was formed to counter the KMT. Martial law was lifted one year later by Chiang Ching-kuo. Chiang selected Lee Teng-hui, a Taiwanese born technocrat to be his Vice President. The move followed other reforms giving more power to Taiwanese born citizens and calmed anti-KMT sentiments during a period in which many other Asian autocracies were being shaken by People Power movements.

Chiang Ching-kuo died in 1988. Chiang's successor, President Lee Teng-hui, continued to hand more government authority over to Taiwanese born citizens. He also began to democratize the government. Taiwan underwent a process of localization, under Lee. In this localization process, local culture and history was promoted over a pan-China viewpoint. Lee's reforms included printing banknotes from the Central Bank instead of the usual Provincial Bank of Taiwan. He also largely suspended the operation of the Taiwan Provincial Government. In 1991 the Legislative Yuan and National Assembly elected in 1947 were forced to resign. These groups was originally created to represent mainland China constituencies. Also lifted were the restrictions on the use of Taiwanese languages in the broadcast media and in schools.

However, Lee failed to crack down on the massive corruption that developed under authoritarian KMT party rule. Many KMT loyalists feel Lee betrayed the ROC by taking reforms too far, while other Taiwanese feel he did not take reforms far enough.

Democratic period

Lee ran as the incumbent in Taiwan's first direct presidential election in 1996 against DPP candidate and former dissident, Peng Min-ming. This election prompted the PRC to conduct a series of missile tests in the Taiwan Strait to intimidate the Taiwanese electorate so that electorates would vote for other pro-unification candidates, Chen Li-an and Lin Yang-kang. The aggressive tactic prompted U.S. President Clinton to invoke the Taiwan Relations Act and dispatch two aircraft carrier battle groups into the region off Taiwan's southern coast to monitor the situation, and PRC's missile tests were forced to end earlier than planned. This incident is known as the 1996 Taiwan Straits Crisis.

One of Lee's final acts as president was to declare on German radio that the ROC and the PRC have a special state to state relationship. Lee's statement was met with the PRC's People's Army conducting military drills in Fujian and a frightening island-wide blackout in Taiwan, causing many to fear an attack.

Peaceful change of political party in power

In the 2000 presidential election marked the end to KMT rule. Opposition DPP candidate Chen Shui-bian won a three way race that saw the Pan-Blue vote split between independent James Soong and KMT candidate Lien Chan. President Chen garnered 39% of the vote.[42]

In 2004, President Chen was re-elected to a second four year term after an assassination attempt which occurred the day before the election. Two shots were fired, one bullet grazing the President's belly after penetrating the windshield of a jeep and multilayers of clothing, the other bullet penetrated the windshield and hitting the vice president's knee cast(She was wearing a knee cast due to an earlier injury). Police investigators have said that the most likely suspect is believed to have been Chen Yi-hsiung, who was later found dead.[43]

In 2007, President Chen proposed a policy of Four Wants and One Without, which in substances states that Taiwan wants independence; Taiwan wants the rectification of its name; Taiwan wants a new constitution; Taiwan wants development; and Taiwanese politics is without the question of left or right, but only the question of unification or independence. The reception of this proposed policy in Taiwanese general public was unclear. It, however, was met with a cold reception by both the PRC and the United States. The PRC Foreign Minister emphasised that the Anti-Secession Law was not a piece of unenforceable legislation, while the US Department of State spokesman Sean McCormack described Chen's policy as "unhelpful".[44]

The KMT retook the office of president when Ma Ying-jeou was elected in March 2008. The party also retained control of the legislature.

A spate of arrests of members of the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has drawn allegations that the Beijing-friendly Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), which once ruled Taiwan under martial law, is back in the business of political repression.

The most controversial are the arrests on allegations of corruption of Chen Shui-bian, Taiwan's former president; Chiou I-jen, a former National Security Council secretary-general; and Yeh Sheng-mao, former director-general of the Ministry of Justice's Investigation Bureau.

"I am extremely concerned about the political situation in Taiwan, and I am personally very angry at the way the current government is handling national affairs and the way our beloved Taiwan is heading: back to the authoritarian past," said Joseph Wu, former de facto Taiwan ambassador to the United States under the Chen administration.[45]

See also

- Timeline of Taiwanese history

- Dutch Empire

- Japanese expansionism

- Japanese opium policy in Taiwan (1895–1945)

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Political status of Taiwan

- Chinese reunification

- Taiwan independence

- Know Taiwan

- Foreign relations of the Republic of China

- Military dependents' village

Notes

- ↑ "Archaeological Theory; Taiwan Seen As Ancient Pacific Rim", Taiwan Journal" published 19 November 1990, URL retrieved 3 June 2007

- ↑ Tainan County Government Information division website (autotranslated from Chinese) last updated 1 September 2006, URL retrieved 3 June 2007

- ↑ Stafford, Peter. 1992. Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Berkeley, California, Ronin Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-914171-51-8

- ↑ Blust, Robert. "Subgrouping, circularity and extinction: some issues in Austronesian comparative linguistics," (1999)

- ↑ Hill et al., "A Mitochondrial Stratigraphy for Island Southeast Asia," (2007); Bird et al., "Populating PEP II: the dispersal of humans and agriculture through Austral-Asia and Oceania," (2004)

- ↑ CIP, "Statistics of Indigenous Population in Taiwan and Fukien Areas," (2006)

- ↑ Zeitoun, Elizabeth and Yu, "The Formosan Language Archive: Linguistic Analysis and Language Processing. (PDF)," (2005)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Blust, (1999)

- ↑ Teng, Emma Jinhuang, Taiwan's Imagined Geography: Chinese Colonial Travel Writing and Pictures, (2004), pg.34-59

- ↑ Teng, (2004) pg.34-49,177-179

- ↑ Mateo, Jose Eugenio Borao. Spaniards in Taiwan Vol. II:1642-1682, (2001), pg.2-9

- ↑ Mateo, (2001) pg.329-333; Blusse, Leonard & Everts, Natalie. The Formosan Encounter: Notes on Formosa’s Aboriginal Society-A selection of Documents from Dutch Archival Sources Vol. I & Vol. II, (2000), pg.300-309

- ↑ Campbell, Rev. William. Sketches of Formosa, (1915); Blusse, Everts, (2000)

- ↑ Shepherd, John R. Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600-1800, (1993), pg.1-29

- ↑ Keliher, Macabe. Out of China or Yu Yonghe's Tales of Formosa: A History of 17th Century Taiwan, (2003), pg.32

- ↑ Shepherd, (1993)

- ↑ Blusse, Everts (2000)

- ↑ Everts, Natalie. "Jacob Lamay van Taywan:An Indigenous Formosan Who Became and Amsterdam Citizen," (2000), pg.151-155

- ↑ Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China (Second Edition), (1999), pg.46-49

- ↑ Clements, Jonathan. Pirate King:Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty, (2004), pg.188-201

- ↑ Spence, (1999), pg.51-57; Clements, (2003), pg.215

- ↑ Guo, Guo, Hongbin. "Keeping or abandoning Taiwan," (2003)

- ↑ Leung, Edwin Pak-Wah. "The Quasi-War in East Asia: Japan's Expedition to Taiwan and the Ryūkyū Controversy," (1983), pg.270

- ↑ Morris, Andrew. "The Taiwan Republic of 1895 and the Failure of the Qing Modernizing Project," (2002), pg.5-6

- ↑ Zhang, Yufa. Zhonghua Minguo shigao(中華民國史稿), (1998), pg.514

- ↑ Government Information Office, "A Brief History of Taiwan: European Occupation of Taiwan and Confrontation between Holland in the South and Spain in the North"

- ↑ Morris, (2002), pg.4-18

- ↑ Katz, Paul. When The Valleys Turned Blood Red: The Ta-pa-ni Incident in Colonial Taiwan, (2005)

- ↑ Zhang, (1998), pg.514

- ↑ Katz, (2005)

- ↑ Ching, Leo T.S. Becoming "Japanese" Colonial Taiwan and The Politics of Identity Formation, (2001), pg137-140

- ↑ Zhang, (1998), pg.515

- ↑ Yosaburo, Takekoshi. Japanese Rule in Formosa, (1997).

- ↑ Kerr, George H., Formosa Betrayed, (1966).

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 [1] UNHCR

- ↑ 「去日本化」「再中國化」:戰後台灣文化重建(1945-1947),Chapter 1. publisher: 麥田出版社, author: 黃英哲, December 19, 2007

- ↑ UK Parliament, May 4, 1955, http://www.taiwanbasic.com/hansard/uk/uk1955as.htm, retrieved 2010-02-27

- ↑ Resolving Cross-Strait Relations Between China and Taiwan, American Journal of International Law, July 2000, http://www.taiwanbasic.com/lawjrn/res-cs1.htm, retrieved 2010-02-27

- ↑ Kerr, (1966), pg.254-255

- ↑ Gates, Hill, "Ethnicity and Social Class," (1981)

- ↑ Chan. "Taiwan as an Emerging Foreign Aid Donor: Developments, Problems, and Prospects," (1997)

- ↑ Asia Society, "Opposition Wins Taiwan Election," (2000)

- ↑ Reuters, "Taiwan election shooting suspect dead," (2005)

- ↑ "US Says Taiwanese President's Independence Remarks 'Unhelpful'". Voice of America. 2007-03-05. http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/library/news/taiwan/2007/taiwan-070305-voa02.htm.

- ↑ defensenews.com

References

- Asia Society, "Opposition Wins Taiwan Election," (2000)|reference=Asia Society, Asia Today. (2000). "Opposition Wins Taiwan Election," March 14, 2000.

- Bird, Michael I, Hope, Geoffrey & Taylor, David (2004). Populating PEP II: the dispersal of humans and agriculture through Austral-Asia and Oceania. Quaternary International 118–119:145–163. Accessed 3/31/2007.

- Blusse, Leonard & Everts, Natalie (2000). The Formosan Encounter: Notes on Formosa’s Aboriginal Society-A selection of Documents from Dutch Archival Sources Vol. I & Vol. II. Taipei: Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines. ISBN 957-99767-2-4 & ISBN 957-99767-7-5

- Blust, R. (1999). "Subgrouping, circularity and extinction: some issues in Austronesian comparative linguistics" in E. Zeitoun & P.J.K Li (Ed.) Selected papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics (pp. 31-94). Taipei: Academia Sinica.

- Borao Mateo, Jose Eugenio (2002). Spaniards in Taiwan Vol. II:1642-1682. Taipei: SMC Publishing

- Brown, Melissa J (1996). "On Becoming Chinese" in Melissa J. Brown (Ed.) Negotiating Ethnicities in China and Taiwan. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Brown, Melissa J. (2001). Reconstructing ethnicity: recorded and remembered identity in Taiwan. Ethnology 40.2

- Brown, Melissa J (2004). Is Taiwan Chinese? : The Impact of Culture, Power and Migration on Changing Identities. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23182-1

- Campbell, Rev. William (1915). Sketches of Formosa. London, Edinburgh, New York: Marshall Brothers Ltd. reprinted by SMC Publishing Inc 1996. ISBN 957-638-377-3

- Chan (1997). 'Taiwan as an Emerging Foreign Aid Donor: Developments, Problems, and Prospects. Pacific Affairs 70.1:37–56.

- Chen, Chiu-kun (1997). Qing dai Taiwan tu zhe di quan, (Land Rights in Qing Era Taiwan). Taipei, Taiwan: Academia Historica. ISBN 957-671-272-6

- Chen, Chiukun (1999). "From Landlords To Local Strongmen: The Transformation Of Local Elites In Mid-Ch'ing Taiwan, 1780-1862" in Rubinstein, Murray A (Ed.) Taiwan : a New history (pp. 133-62). Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe.

- Ching, Leo T.S. (2001). Becoming "Japanese" Colonial Taiwan and The Politics of Identity Formation. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22551-1

- Chu, Jou-juo (2001). Taiwan at the end of The 20th Century:The Gains and Losses. Taipei: Tonsan Publications

- Council of Indigenous Peoples. (2004). Table 1. Statistics of Indigenous Population in Taiwan and Fukien Areas for Townships, Cities and Districts. Accessed 3/18/2007.

- Clements, Jonathan (2004). Pirate King:Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. United Kingdom: Muramasa Industries Limited

- Cohen, Marc J. (1988). Taiwan At The Crossroads: Human Rights, Political Development and Social Change on the Beautiful Island. Washington D.C.: Asia Resource Center.

- Copper, John F. (2003). Taiwan:Nation-State or Province? Fourth Edition. Boulder, CO: Westview Press

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1999). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23424-3

- Council of Indigenous Peoples, Executive Yuan. (2006). "Statistics of Indigenous Population in Taiwan and Fukien Areas".

- Dikotter, Frank (1992). The Discourse of Race in Modern China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2334-6

- Ebrey, Patricia (1996). "Surnames and Han Chinese Identity" in Melissa J. Brown (Ed.) Negotiating Ethnicities in China and Taiwan. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 1-55729-048-2

- Edmondson, Robert (2002). "The February 28 Incident and National Identity" in Stephane Corcuff (Ed.) Momories of the Future:National Identity Issues and the Search for a New Taiwan. New York: M.E. Sharpe

- Everts, Natalie (2000). "Jacob Lamay van Taywan:An Indigenous Formosan Who Became and Amsterdam Citizen" in Ed. David Blundell; Austronesian Taiwan:Linguistics' History, Ethnology, Prehistory. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Faure, David (2001). In Search of the Hunters and Their Tribes. Taipei: Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines Publishing. ISBN 957-30287-0-0

- Frederic, Louis (2002). "Ryūkyū kizoku mondai" in Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Gates, Hill (1981). "Ethnicity and Social Class" in in Emily Martin Ahern and Hill Gates The Anthropology of Taiwanese Society. CA:

- Gao, Pat (2001). Minority, Not Minor. Website of Government Information Office, Republic of China. Accessed 3/22/2007.

- Gold, Thomas B. (1986). State and society in the Taiwan miracle. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe.

- Government Information Office, "A Brief History of Taiwan," (2007)|reference=Government Information Office, Republic of China. "A Brief History of Taiwan: European Occupation of Taiwan and Confrontation between Holland in the South and Spain in the North".

- Guo, Hongbin (2003). Keeping or abandoning Taiwan. Taiwanese History for the Taiwanese. Taiwan Overseas Net. Accessed 08-11 2007.

- Harrell, Steven (1996). "Introduction" in Melissa J. Brown (Ed.) Negotiating Ethnicities in China and Taiwan (pp. 1-18). Berkeley, CA: Regents of the University of California.

- Harrison, Henrietta (2001). "Changing Nationalities, Changing Ethnicities: Taiwan Indigenous Villages in the Years after 1946" in David Faure (Ed.) In Search of the Hunters and Their Tribes: Studies in the History and Culture of the Taiwan Indigenous People. Taipei: SMC Publishing.

- Harrison, Henrietta (2001). Natives of Formosa: British Reports of the Taiwan Indigenous People, 1650-1950. Taipei: Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines Publishing. ISBN 957-99767-9-1

- Harrison, Henrietta (2002). "Changing Nationalities, Changing Ethnicities" in David Faure (Ed.) In Search of the Hunters and Their Tribes: Studies in the History and Culture of the Taiwan Indigenous People. Taipei: SMC Publishing.

- Harrison, Henrietta (2003). Clothing and Power on the Periphery of Empire: The Costumes of the Indigenous People of Taiwan.. positions 11.2:331-60.

- Hattaway, Paul (2003). Operation China. Introducing all the Peoples of China. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library Pub. ISBN 0-87808-351-0

- Hill, Catherine, Soares, Pedro & Mormina, Maru, et al. (2007). A Mitochondrial Stratigraphy for Island Southeast Asia. American Journal of Human Genetics 291:1735–1737.

- Hong, Mei Yuan (1997). Taiwan zhong bu ping pu zhu (Plains Tribes of Central Taiwan). Taipei, Taiwan: Academia Historica.

- Hsiau, A-chin (1997). Language Ideology in Taiwan: The KMT’s language policy, the Tai-yü language movement, and ethnic politics. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 18.4.

- Hsiau, A-chin (2000). Contemporary Taiwanese Cultural Nationalism. London: Routledge

- Hsu, Cho-yun (1980). "The Chinese Settlement of the Ilan Plain" in Ronald Knapp (Ed.) China's Island Frontier: Studies in the Historical Geography of Taiwan. HA: University of Hawaii Press.

- Keliher, Macabe (2003). Out of China or Yu Yonghe's Tales of Formosa: A History of 17th Century Taiwan. Taipei: SMC Publishing

- Hsu, Wen-hsiung (1980). "Frontier Organization and Social Disorder in Ch'ing Taiwan" in Ronald Knapp (Ed.) China's Island Frontier: Studies in the Historical Geography of Taiwan. HA: University of Hawaii Press.

- Ka, Chih-ming (1995). Japanese Colonialism in Taiwan:Land Tenure, Development and Dependency, 1895-1945. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Katz, Paul (2005). When The Valleys Turned Blood Red: The Ta-pa-ni Incident in Colonial Taiwan. Honolulu, HA: University of Hawaii Press

- Kang, Peter (2003). "A Brief Note on the Possible Factors Contributing to the Large Village Size of the Siraya in the Early Seventeenth Century" in Leonard Blusse (Ed.) Around and About Formosa. Taipei: .

- Kerr, George H (1966). Formosa Betrayed. London: Eyre and Spottiswood.

- Kleeman, Faye Yuan (2003). Under An Imperial Sun: Japanese Colonial Literature of Taiwan and The South. Honolulu, HA: University of Hawaii Press.

- Knapp, Ronald G (1980). "Settlement and Frontier Land Tenure" in Ronald G.Knapp (Ed.) China’s Island Frontier: Studies in the Historical Geography of Taiwan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 957-638-334-X

- Kuo, Jason C. (2000). Art and Cultural Politics in Postwar Taiwan

- Lamley, Harry J (1981). "Subethnic Rivalry in the Ch'ing Period" in Emily Martin Ahern and Hill Gates (Ed.) The Anthropology of Taiwanese Society (pp. 283-88). CA: Stanford University Press.

- Leung, Edwin Pak-Wah (1983). The Quasi-War in East Asia: Japan's Expedition to Taiwan and the Ryūkyū Controversy. Modern Asian Studies 17.2.

- Liu, Tan-Min (2002). ping pu bai she gu wen shu (Old Texts From 100 Ping Pu Villages). Taipei: Academia Sinica. ISBN 957-01-0937-8

- Liu, Tao Tao (2006). "The Last Huntsmen's Quest for Identity: Writing From the Margins in Taiwan" in Yeh Chuen-Rong (Ed.) History, Culture and Ethnicity: Selected Papers from the International Conference on the Formosan Indigenous Peoples (pp. 427-430). Taipei: SMC Publishing

- Matsuda, Kyoko (2003). Ino Kanori's 'History' of Taiwan: Colonial ethnology, the civilizing mission and struggles for survival in East Asia.. History and Anthropology 14.2:179-196

- Mendel, Douglass (1970). The Politics of Formosan Nationalism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Meskill, Johanna Menzel (1979). A Chinese Pioneer Family: The Lins of Wu-Feng, Taiwan 1729-1895. Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Millward, James (1998). Beyond The Pass: Economy, Ethnicity and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864. Stanford CA.: Stanford University Press

- Morris, Andrew (2002). "The Taiwan Republic of 1895 and the Failure of the Qing Modernizing Project" in in Stephane Corcuff (Ed.)Memories of the Future:National Identity issues and the Search for a New Taiwan. New York: M.E. Sharpe Inc.

- Pan, Da He (2002). pingpu bazai zu cang sang shi (The Difficult History of the Pazih Plains Tribe). SMC Publishing. ISBN 957-638-599-7

- Pan, Ying (1996). Taiwan pingpu zu shi (History of Taiwan's Pingpu Tribes). Taipei: SMC Publishing. ISBN 957-638-358-7

- Interview: 2003: Pan Jin Yu (age 93) -in Puli

- Phillips, Steven (2003). Between Assimilation and Independence:The Taiwanese Encounter Nationalist China, 1945-1950. Stanford California: Stanford University Press.

- Pickering, W.A. (1898). Pioneering In Formosa. London: Hurst and Blackett. Republished 1993, Taipei, SMC Publishing. ISBN 957-638-163-0.

- Reuters, "Taiwan election shooting suspect dead," (2005)|reference=Reuters. "Taiwan election shooting suspect dead," March 7, 2005.

- Rubinstein, Murray A (1999). Taiwan: A New History. New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. ISBN 1-56324-816-6

- Shepherd, John R. (1993). Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600-1800. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.. Reprinted 1995, SMC Publishing, Taipei. ISBN 957-638-311-0

- Shepherd, John Robert (1995). Marriage and Mandatory Abortion among the 17th Century Siraya.

- Simon, Scott (2006, Jan 4). "Formosa's First Nations and the Japanese: from Colonial Rule to Postcolonial Resistance". Japan Focus. Accessed 3/16/2007.

- Skoggard, Ian A. (1996). The Indigenous Dynamic in Taiwan's Postwar Development: Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship. New York: M.E.Sharpe Inc.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999). The Search for Modern China (Second Edition). U.S.A.: W.W. Norton and Company

- Stainton, Michael (1999). "The Politics of Taiwan Aboriginal Origins" in Murray A. Rubinstein (Ed.) Taiwan A New History. New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. ISBN 1-56324-816-6

- Takekoshi, Yasaburo (1907). Japanese Rule in Formosa. London: Longmans and Green & Company

- Teng, Emma Jinhuang (2004). Taiwan's Imagined Geography: Chinese Colonial Travel Writing and Pictures, 1683-1895. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN=0-674-01451-0

- Tseng, Ching-Nan, Zhang, W. & Chang, Weien (1993). In search of China's Minorities. Beijing: China Books & Periodicals.

- Watchman, Alan M. (1994). Taiwan:National Identity and Democratization. New York: M.E.Sharpe Inc.

- Wilson, Richard W (1970). Learning To Be Chinese: The Political Socialization of Children in Taiwan. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Yosaburo, Takekoshi (1997). Japanese Rule in Formosa. Taipei: Longman's Green and Company

- Zeitoun, Elizabeth & Yu (2005). "The Formosan Language Archive: Linguistic Analysis and Language Processing. (PDF)". Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing 10.2:167-200.

- Zhang, Yufa (1998). Zhonghua Minguo shigao(中華民國史稿). Taipei, Taiwan: Lian jing (聯經). ISBN 957-08-1826-3

External links

- Taiwan's 400 years of history, from "Taiwan, Ilha Formosa" (a pro-independence organization)

- Reed Institute's Formosa Digital Library

- History of Taiwan from FAPA (a pro-independence organization)

- Taiwan History China Taiwan Information Center (PRC perspective)

- Museum Fort San Domingo Exhibition in Tamsui about the Dutch history of Taiwan

- Taiwan Memory-Digital Photo Museum Taiwan old photos digital museum plan (Chinese)

- America and Taiwan, 1943-2004

- Formosa Betrayed by George H. Kerr

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||